How Dollar Shave Club's Founder Built a $1 Billion Company That Changed the Industry

Michael Dubin occasionally allowed himself to envision the moment when everything paid off. He’d be ushered into a grand ceremony, where some conglomerate, eager to own his massively successful company, would offer him a fortune for the pleasure. “I thought we would pass a really nice pen around in a wood-paneled boardroom with portraits of men with white hair,” he says.

When the moment actually came, on July 19, 2016, there was none of that. He was in his pajamas, lying on a bed at the Skytop Lodge in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania. His lawyers had been working through the night, and now the sun was up and Dubin had his cellphone pressed to his ear. In two hours, he was set to take the stage in the hotel’s ballroom, where leaders of the multinational conglomerate Unilever would gather for its biannual conference. There, they’d announce that he was now part of their team: Dollar Shave Club was being acquired for $1 billion. But first, the deal had to be finalized. Dubin listened as, one by one, the executives on the phone gave their approval. Then it came down to him.

Today, Dubin swears he hadn’t been looking to sell the company so early. (He declines to say whether other offers had come along.) The way he saw it, his five-year-old Dollar Shave Club was only getting started. When he launched it in 2012, the razor market was dominated by Gillette, which claimed 72 percent of the U.S. market and had been purchased by Procter & Gamble for $57 billion in 2005. Schick was a distant second. But Dubin saw an opening. He could start by undercutting the big competitors on razors, and then build out something that felt less like a shaving supply company and more like a full-scale men’s club -- a subscription-based grooming brand with personality, that men actually identify with.

“If anyone else had brought me the idea, I would have said, ‘Well, it’s a tough category with lots of global competitors,’” says venture capitalist Kirsten Green, founder of Silicon Valley-based Forerunner Ventures. But Dubin quickly convinced her to be one of his company’s early investors. Spend any time with Dubin and it’s easy to understand why. Tall, sandy-haired and preppy, the 38-year-old entrepreneur can vacillate between guy’s-guy sarcasm and serious, intense shop talk. He’s also a voracious reader, giving every new employee copies of two of his favorite books: Thich Nhat Hanh’s How to Sit and Peter Drucker’s The Effective Executive. “Within the first 10 minutes of meeting Michael, I was completely drawn into his idea and vision and him,” Green says.

In the years that followed, Dollar Shave Club released a full range of products, made a name for itself with viral online videos and produced the kind of growth rarely seen in the once sleepy category of men’s grooming. Other mail-order companies, such as Harry’s and ShaveMOB, entered the space, and Amazon got into the game as well. By 2015, four years after Dubin began, web sales for men’s shaving gear had more than doubled industry-wide, to $263 million -- and the following year, Dollar Shave Club was the number one online razor company, with 51 percent of the market, compared with Gillette’s 21.2 percent, according to research firm Slice Intelligence. This clearly spooked the industry giant; Gillette launched its own Gillette Shave Club and bought promoted tweets to claim things like “two million guys and counting no longer buy from the other shave clubs.” But Dubin’s company kept growing, more than doubling its revenue every year since launching. It started with $6 million in 2012 and is on track for more than $250 million this year.

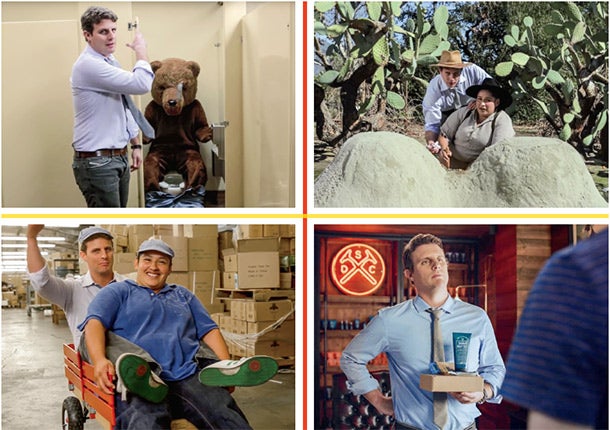

Photo stills courtesy of Dollar Shave Club

Still, the sale to Unilever was a detour from his initial roadmap. He hadn’t built Dollar Shave Club for a quick cash-out. He thought his company could become “a brand that sits on the shelf next to the Starbucks and the Nikes and the Red Bulls of the world,” he says, and he wanted to be the one to lead it there. That meant Dollar Shave Club must retain what made it special -- its culture, its voice and its free spirit. But would his then-205 employees and three million-plus members, who were attracted to its lovable scrappiness, still feel that connection once the startup became part of a corporate giant? “I think it’s always a concern of a founder,” Dubin says. “The most important aspect of culture is how people feel about their role. You need clear financial and spiritual objectives and benefits. If you don’t get that right, it doesn’t matter how many beanbag chairs you have.”

The company’s open floor plan in a Los Angeles suburb doesn’t have beanbag chairs at all, actually, but it does have a strong culture of communal fun and a tireless work ethic: free lunch on Tuesday, events like bouquet making on Valentine’s Day and PlayStation and Nintendo boxes beneath a neon sign in pink cursive that says get back to work. (“That’s a bit of our dry humor,” says spokeswoman Kristina Levsky.)

Related: Learn the Traits of Successful CEOs

Unilever, however, promised that the company he built would stay the same -- and he would have the financial freedom to truly achieve his vision. So in the hotel room, still in his pajamas, Dubin flipped open his laptop and brought up DocuSign. The $1 billion contract appeared in front of him. He clicked OK. Sale finalized. Then DocuSign’s standard message popped up: “You’re done signing. A copy of this document will be sent to your email address when completed by all signers. You can also download or print using the icons above.”

“I took a screenshot,” Dubin says, “because it was so unceremonious.”

A few hours later, as planned, Dubin went onstage to be introduced as Unilever’s newest leader. Then he and Unilever’s president of North American operations, Kees Kruythoff, flew to Los Angeles to tell Dollar Shave Club’s employees. As Dubin recalls, “He said, ‘Congratulations; you just bought Unilever,’ which was his way of saying it was important for us to maintain our culture.”

Dubin had taken the company this far. Now everyone looked to him to keep it going.

Dubin grew up in Bryn Mawr, Pa., not far from the Pocono Mountains, where he signed that deal of a lifetime. After graduating from Emory University, he moved to New York City, where he took several jobs in marketing and advertising, seeking work in the smaller, more nimble business units of companies including NBCUniversal and Time Inc. “I like molten environments that have yet to harden, because it allows you the opportunity to have a voice and to shape things, and I do think that I’m a good shaper of things,” he says. At night, he took classes in accounting, corporate finance and comedy improvisation, a combination that helped him see business as a fluid, ever-changing space. “One of the tenets of improv is to use what’s given to you and make the most out of it,” he says. “You can’t be overly precious about the way you had outlined things in your head at the beginning of a venture.”

In 2011, Dubin met a friend’s father-in-law at a party. Over cocktails, the man told Dubin that he needed to unload a warehouse full of surplus razor blades. Dubin’s improv instincts kicked in; he offered to help. Dubin thought about his long-standing irritation with the razor-buying process -- go to the store, ask a salesclerk to open the plexiglass-encased “razor fortress” and pay more than seems reasonable for a small pack of blades. If he could mail blades to customers for a lower price, he reasoned, men would appreciate the problem he was solving. And from there, the opportunity only got bigger.

“American men are evolving in their bathroom routine,” Dubin says. “Five years ago, if you spent time in front of the mirror, people would have called you a metrosexual. We now live in the age where it’s OK to hug guys and compliment and give advice.” But while some major brands had shifted to serving those guys -- Axe shook off its bro image, Old Spice rebooted its marketing and Dove launched a line of men’s products with a 2010 Super Bowl ad -- nobody had tried to build a community around affordable men’s grooming products. Dubin thought he could.

He registered the domain dollarshaveclub.com within a week and began sketching out his notion for a grooming empire. A few months later, he quit his job to work on it full-time. And on March 6, 2012, at 6 a.m. Pacific time, he published a video that announced Dollar Shave Club to the world and would establish the voice it always spoke in. It opens on Dubin at a desk, pitching his razors. But then he stands up and walks with a swagger. “Are the blades any good?” he asks. “No.” Then he stops next to a sign that says our blades are f***ing great -- and from there, the video turns into a self-aware, shticky, hilariously slapstick pitch, with Dubin wielding a machete, driving a forklift and dancing with a guy in a bear costume while scattering dollar bills into the air with a leaf blower. It cost $4,500 to make, which came out of Dubin’s meager savings, and it proved an instant success. The company took 12,000 orders that day. The video has since been watched 24 million times on YouTube.

“It spoke to a psychographic that wants to take life lightly,” says Olivier Toubia, a Columbia Business School professor who teaches the video as a case study. “Sometimes customers just want something simple.” This was an audience that the likes of Gillette had overlooked, with its self-serious, high-tech blades and vibrating handles. And Dubin, relying on the insights he’d learned by working in marketing, intentionally timed the release for maximum impact -- just before South By Southwest, when reporters were in a lull waiting for big digital news to break. He coupled the video’s launch with the announcement that his company had closed $1 million in seed funding, so, Dubin says, “the tech press picked it up first, and then the mainstream press picked it up from there. At that point it was viral.”

Even at the start, when Dollar Shave Club was functionally a one-man operation selling surplus blades, Dubin wanted to pay off on the “club” part. What could he offer, aside from a mail-order product? He decided to designate himself the company’s first “Club Pro.” It was a spin on customer service; rather than just helping people with their orders, a Club Pro would be on hand to answer any grooming questions -- a kind of on-call concierge, available by email, phone, text, online chat or social media. If a man somewhere wondered why his skin was red on the days he didn’t shave, Dubin would find the answer.

Once Dubin hired a few employees, he and a small team began traveling the country to learn more about people’s grooming habits. They focused on regional events like the Maine Lobster Festival and the Gilroy Garlic Festival -- places where grooming conversations weren’t exactly the norm. The point was to meet average guys on their turf and learn what they wanted. “We figured out how to talk to people, not at them,” says Cassie Jasso, one of the company’s first 10 hires.

Dubin was eager to expand into other products, but the festivals taught him that he couldn’t just start stocking his digital shelves. Men were happy to talk about grooming, but they weren’t always knowledgeable or adventurous about it. To succeed, Dollar Shave Club would have to be more than a voice -- it would have to be the leader of a conversation, and an educator that men actually wanted to hear from.

At 10 a.m. on a Tuesday morning this past January, Dubin is presiding over a glass-enclosed conference room in the modern, low-slung warehouse in Marina del Rey, Calif., that Dollar Shave Club has occupied since 2015. Eight members of the company’s creative team have convened for a brainstorming session; they want to script a video that explains their sulphate-free soap and hairstyling products.

The company has expanded into more than 30 products across five categories, and promoted them with hundreds of funny videos for TV, YouTube and its own website. Dubin still stars in some, but other staffers get camera time as well. Today the group considers Fadi Mourad, the company’s gregarious, tattooed chief innovation officer, who is responsible for developing new products.

“What if we dressed Fadi as Clippy from Microsoft?” someone suggests, and then makes his voice squeaky to impersonate the software’s much-maligned paper clip mascot. “Hmm … looks like you’re buying shampoo!”

They run through several more scenarios: Fadi as mad scientist, Fadi as zany Swedish chef. Someone proposes a cooking show format where Fadi shows how shave butter is made.

“Bingo,” Dubin says. “I love that. I think that’s a really fun format to play with. I like the juxtaposition of the scientist with the average guy. That cuts to the heart of the brand and who we are.”

That sense of brand -- and of what people expect from it -- has steered not just the company’s marketing but its product development as well. It took Mourad some time to adjust to it. He had spent 15 years developing products for Estée Lauder and Bumble and Bumble and was used to long meetings where trend forecasters would dissect runway shows and fashion magazines. “My first executive meeting here was eye-opening because nobody cared what those trends were,” says Mourad. Instead, the company often turned to regular guys to say what they needed, what they were excited to try, and what basics could be improved upon. “That’s never how I would have started the innovation process anywhere else.”

Much like its foray into oddball festivals, Dollar Shave Club began this process with a lot of small consumer panels. “We talk through the ‘shit, shave and shower’ routine with our customers and uncover pain points,” Mourad says. Surprising ideas would come out of these, like when one panel began complaining about rough toilet paper. From this, the company created its popular One Wipe Charlies, a flushable, moist cloth it bills as the “#1 way to clean up after #2.” “No trend would have told you that guys are looking for butt wipes,” Mourad says. (Meanwhile, when beard oils and dry shampoos briefly became a thing, Dollar Shave Club passed; its panels just didn’t seem interested.) This saves Dollar Shave Club a lot of hassle. About 80 percent of the products it tries out eventually make it to market.

Of course, this doesn’t mean the company always hits the bull’s-eye. Last year, it launched an exfoliating cloth marketed to men as a “shower tool,” but the reviews weren’t great. “We didn’t hide the reaction,” says chief marketing officer Adam Weber, who previously worked at Procter & Gamble and Gilt Groupe. “We had a very transparent conversation with our customers and redesigned it in less than two weeks.” Then they sent a refund to all 64,000 members who bought the old version, even if they hadn’t asked for one.

“That was the moment we realized we needed a much bigger member panel,” Weber says. Its other panels had helped products develop, but Dollar Shave Club had no way of testing products once they actually existed. Last year, it created a 500-member, invite-only group of long-standing customers. They now test new products and give instant feedback, which Weber says has helped the company overall. “It creates a sense of urgency to react faster,” he says.

For the three million-plus customers who aren’t in that little group, Dollar Shave Club is continually seeking ways to engage them with more than just sales pitches. It has hired writers and editors to create MEL, an online men’s lifestyle magazine; a funny pamphlet called “Bathroom Minutes,” which comes in every delivery; and the company’s podcast, which tackles topics such as “Why Is Everyone on the Internet So Angry?” and “Which Body Parts Can You Actually Grow Back?” And although Dubin long ago stopped having time to personally answer customers’ grooming questions, he’s replaced himself with more than 100 Club Pros, who now work out of the company’s headquarters.

In fact, as the company continued to grow, Dubin was increasingly being drawn away from the club members he’d courted. “I went out and raised money every 12 months, which takes three months at the very least and becomes your number one, all-consuming priority,” Dubin says. It’s something every startup CEO has to deal with, of course. But then an unexpected conversation had him envisioning a very different routine.

In 2015, when Dubin was interviewing investment banks to help raise Series D funding, he met J.P. Morgan managing director Romitha Mally. Shortly after, Mally ran into her friend Kees Kruythoff, president of Unilever’s North American operations, at the Virgin Atlantic lounge at Heathrow. “I told him about this amazing company we just raised money for, a 21st-century men’s grooming platform with sticky customers,” she says.

Intrigued, Kruythoff asked to meet Dubin. The three of them had dinner at the Mandarin Oriental hotel in New York. “There was instant chemistry between the two of them,” Mally says. There was synergy between the companies, too. Both men saw the possibilities in combining the resources of a multinational conglomerate with a disruptive innovator. Dubin thought he could recruit Kruythoff to serve in an advisory role or on Dollar Shave Club’s board.

Unilever had a bigger vision. Five months after that dinner, Unilever called Mally after seeing Dollar Shave Club’s Super Bowl commercial to say it wanted to buy the company. Unilever was especially interested in the company’s substantial trove of customer data and potential to scale globally. “Most consumer packaged-goods companies distribute through a retailer, so you never know who your best customers are,” Mally says. “But Michael found a powerful way to connect directly with the consumer.”

The offer flattered Dubin. And the more he sat with it, the more he liked it. Unilever was offering to keep everything the same: Dubin and his company would stay in Marina del Rey, under his leadership. And with Unilever’s money, Dubin would be freed up to focus on growing the business at a rate he couldn’t have imagined before. “When we began the discussions with Unilever, I thought, Wow, what could I do with 25 percent more of my time? What amazing results we could have,” Dubin says. “We didn’t want to open this up to competitive bidding. At a certain point, it became too attractive to say no.”

“Excuse me?” A guy with long hair and a beard bends over our table. “Are you the founder of Dollar Shave Club?” Dubin nods; this happens regularly, ever since his first viral video made him an internet star. “Love what you did with the razors,” the guy says, proffering a fist bump before walking away.

We are at Superba Food + Bread, a casual breakfast spot in Dubin’s Venice, Calif., neighborhood that he visits most mornings before heading into the office. He knows the secret parking spots and usually has a black coffee waiting for him on the counter. As the man walks away, Dubin sizes up his grooming habits. “He looked like the kind of guy who uses an electric razor,” Dubin says. “He had great hair, so he must use our amazing hair products.”

Dubin is feeling relaxed these days. He’s loving the life of a CEO who doesn’t fundraise or worry about running out of money. “The ability for me to focus more completely on operations and running the business has de-stressed me a bit,” he says. And he’s energized by planning Dollar Shave Club’s next big move: international expansion. The company already operates in Canada and Australia, and is now plotting its footprint in Europe and Asia.

New cultures will create new challenges for Dollar Shave Club. After all, the company grew by keenly understanding the American man. Now it will have to dissect very different cultures, with very different grooming standards. But Dubin’s team treats this as liberating -- allowing it to follow new paths and enter new product categories, all while following the same instincts Dubin used to grow the company in the first place. “Michael can look into the future better than anyone I’ve ever met,” Weber, the CMO, says. “Some people call it luck, but I think Michael has a very good sense of when to do what. There’s no set template. You can’t go and buy the playbook.”

So what’s next? The conversations inside Dollar Shave Club may shock the average dude. Hair color. Vitamins. Some are even talking about men’s color makeup, something Mourad, the innovation officer, truly believes American men will soon want. But if those guys take a while to come around, that’s fine: Dollar Shave Club can now hone those products in more fashion-forward countries. And one day, when guys here are ready for makeup, Dollar Shave Club will probably do what it does best: make a video that transforms a quiet category into something surprisingly special.

Comments

Post a Comment